News

Backgrounder: The AMA (WA) again calls for the introduction of low-level social restrictions

Tuesday January 25, 2022

To be attributed to AMA (WA) President Dr Mark Duncan-Smith:

The following provides some context through current research to support the AMA (WA) stance and refute assertions by Premier Mark McGowan suggesting social restrictions now could be damaging.

Early action is better than late reaction.

In general terms, once an outbreak has started, the earlier social restrictions are put in place, the more effective they are.

Milne (2021a) opines restrictions will still be required in high vaccine populations,and should be activated as soon as case numbers start to increase.

Kompas et al (2021) concluded that early rather than late suppression leads to the lowest estimated public health and economy costs.

Although referring to travel, Graesboll et al (2021) stressed the need for the restrictions to be introduced fast and in the early phases of an outbreak.

Milne (2021b) concluded that social restrictions should be introduced as early as possible.

No evidence that early moderate social restrictions lead to later non-compliance

My recommendations for early moderate restrictions, on Monday and Friday last week similar to South Australia, have been rejected on the basis that they will lead to non-compliance in the future.

I can find no evidence in the literature to support this position. I concede prolonged or unnecessary lockdown may result in this, but a lockdown is not being called for.

Hills and Eraso (2021), Nivette et al (2021) and Kleitma (2021) identify the main factors that related to compliance and non-compliance with social restrictions related to:

Compliant

- vulnerability to the disease

- perceived health benefit

- females

- older

- worry and anxiety about COVID

Non-compliant

None of the studies mention low-level restriction, or timing but I concede they may have not been set up to consider that aspect.

Social restrictions do reduce the peak of a pandemic outbreak

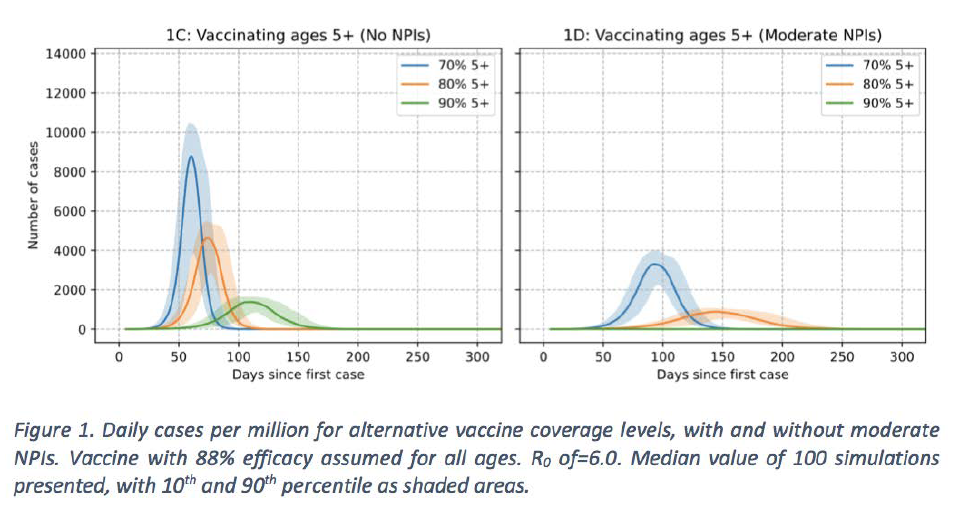

Although it is established that social restrictions will reduce the peak of a COVID outbreak, Milne (2021a) showed this specifically for WA in his modelling for Delta.

Although quantitative information cannot be extrapolated to Omicron, the qualitative effect of reducing the peak is still valid.

NPI = non-pharmacological interventions that include social restrictions.

Requirement to increase restrictions in WA

The later social restrictions are introduced, the less effect they have on reducing the peak, and the sooner the peak will occur.

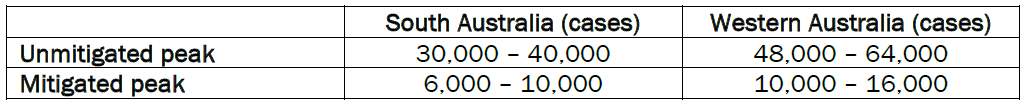

Based on modelling from South Australia by Professor Joshua Ross at Adelaide University, WA may face more than 60,000 cases of COVID-19 per day if we do not introduce restrictions. The modelling, which was based on the Omicron variant, was described by the South Australian Premier as “alarmingly accurate”.

Factoring in the population correction,1 the data indicates the following scenario in Western Australia:

The infectivity of Omicron is three times’ Delta, and although the hospitalisation rate for Omicron is less than Delta, it is significantly less than three times’ the hospital admission rate. Therefore, the sheer number of cases of Omicron will lead to an increased number of hospital admissions, compared to Delta.

Delta modelling cannot be used for Omicron.

It is critical that WA makes decisions based on Omicron modelling and introduces early modest restrictions, similar to current South Australian Level 1 restrictions. These relatively modest restrictions include, for example:

• Density restrictions on hospitality;

• Masks indoors;

• Maximum 10 people at home;

• Dancing allowed at weddings only (not nightclubs or other events); and

• Work from home if at all possible.

1 The population of WA is 2.7 million and the population of SA is 1.7 million. Correction factor for population correction is 1.588 (= 2.7 / 1.7).

References

Græsbøll K et al 2021. Delaying the peak of the COVID-19 epidemic with travel restrictions. Epidemiologic Methods, vol. 10, no. s1, 2021, pp. 20200042. https://doi.org/10.1515/em-2020-0042

Hills, S., Eraso, Y. 2021. Factors associated with non-adherence to social distancing rules during the COVID-19 pandemic: a logistic regression analysis. BMC Public Health 21, 352 (2021) https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10379-7

Kleitman S et al 2021. To comply or not comply? A latent profile analysis of behaviours and attitudes during the COVID-19 pandemic.PLOS published: July 29, 2021 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0255268

Kompas T et al 2021. Health and economic costs of early and delayed suppression and the unmitigated spread of COVID-19: The case of Australia. PLOS, June 4, 2021,

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0252400

Milne et al 2021. Non-pharmaceutical interventions and vaccinating school children required to contain SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant outbreaks in Australia: a modelling analysis: https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.10.03.21264492

Milne GJ et al 2021 A modelling analysis of the effectiveness of second wave COVID-19 response strategies in Australia. Scientific Reports 2021; 11(1): 11958.

Nivette A et al 2021. Non-compliance with COVID-19-related public health measures among young adults in Switzerland: Insights from a longitudinal cohort study. Social Science & Medicine, Volume 268,2021,113370,ISSN 0277-9536, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113370.

ENDS

Please contact AMA (WA) Media via email media@amawa.com.au for further information on this issue.