Blog

SOMETHING OLD, SOMETHING NEW, SOMETHING BORROWED, SOMETHING BLUE: Ideas for Aboriginal primary health system development

Friday December 3, 2021

In a series of annual report cards, the AMA has made significant contributions to strategic directions for Aboriginal health. To these invaluable reports that members are urged to re-read, this article adds complementary ideas from respected leaders and academics for system development in Aboriginal primary healthcare (PHC).

PHC WORKFORCE

Imagine the PHC system as steel meshing that underpins the rest of the Australian healthcare system. This meshing is part of the universal infrastructure that makes the rest of the health system affordable and sustainable.

But what happens when the meshing is weak, torn and rusty? It holds nothing. When new weight is poured onto weak meshing, everything collapses.

What does a strong, well-designed PHC system look like?

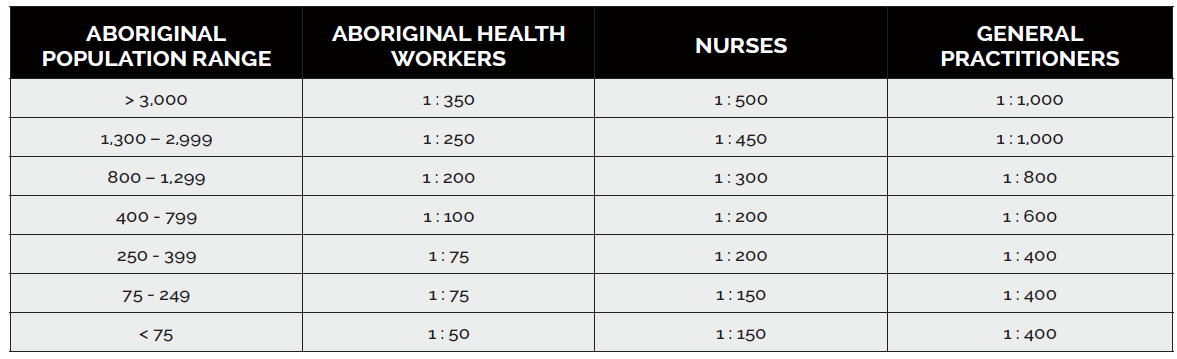

In 2012, the Kimberley Aboriginal Health Planning Forum described service standards for remote Aboriginal communities in the Kimberley based on population size

(see box below).

In a similar vein, One21Seventy based at the Menzies Research Centre in Darwin was a national quality improvement program for PHC, which provided feedback to services in every jurisdiction on their workforce benchmarked against ideal staff to population ratios by community size (last calculated in 2000; see table on page 22).

As the Prime Minister has requested a ‘refresh’ of the nation’s ‘Closing the Gap’ targets for Aboriginal advancement, the need to update workforce standards for contemporary PHC is urgent. Combined with recent research showing high turnover of staff in remote settings, we have enough evidence to act.

ANTI-FRAGILE?

In the latest Productivity Report released January 2018, rates of potentially preventable hospitalisations (PPHs) in Western Australia show how much further we have to go.

Discrepancies between the rates for Aboriginal populations compared with non-Aboriginal populations shine the harshest light on the fragility of the current PHC system.

An alternative approach, based on the concept of the ‘anti-fragile’ health system, is more imaginative and delivers material benefit for community health.

As reported to the Federal AMA CoGP meeting in Canberra in October 2017, Dr Denis Lennox’s warnings were well-heeded that any fracture or siloing of service

or workforce in remote settings serves to further reduce service and workforce size, thereby increasing fragility and risk of failure.

HEALTHIER COMMUNITIES, HEALTHIER STATE

As a basic principle, remote communities of a similar size and distance from town-based services should have equivalent levels of service, regardless of who their preferred service provider is. At a minimum, the Kimberley Aboriginal Health Planning Forum (KAHPF) recommends:

• Communities with regular populations of over 250 should have an onsite health service with an on-call capacity.

• Communities with a regular population of between 100 and 250 should have an onsite health clinic staffed by two health professionals, either Senior Aboriginal Health Workers (SAHW) or Registered Nurses (RN).

• Communities with a regular population of 50-100, which are not within easy access of a community or town clinic should have a fortnightly visit by a health team.

• Communities with regular populations of less than 50 should be serviced on an as-needed basis.

HEALTHY EQUITY & SOCIAL DETERMINANTS

Why does former Australian of the Year, Professor Fiona Stanley, want to change the date of Australia Day?

In her words, just recognition of our shared history with Aboriginal people would have an “almost direct, positive impact on Aboriginal health”.

As Prof Stanley has said, “One of our Aboriginal researchers has got data to show that even young kids, Aboriginal kids, their self-esteem is partly due to how they perceive the dominant culture perceives them.”

Aboriginal leaders have used the metaphor of the mouse and the elephant. Aboriginal communities hold the size and influence of mice compared with the institutional gravitas, connections, capital and elephant-sized power of almost everything – and everyone – else.

This is not an inherent imbalance. New Zealand and Canada have taken huge strides in this regard and the health ‘payoff’ is already visible. To invert the power differential, open up decision-making at every level to Aboriginal people.

The World Bank has shown through persuasive experimental trials that communities receiving data with which they themselves can monitor the quality and impact of services benefit more from these services than those kept in the dark. Community-based monitoring works.

HOLD THE COURSE

Everyone in WA seeks better health for Aboriginal people living in remote and very remote parts of our State. PHC is part of the essential fabric an organised society offers to its citizens. Let’s pick up ideas for system development, which are ready to go and make 2018 a year to remember.