Blog

Appetite for change

Thursday November 11, 2021

The recent commitment to fund additional eating disorder services in WA’s public health system is welcome, but is it enough to meet escalating demand, asks Jenna Cowie.

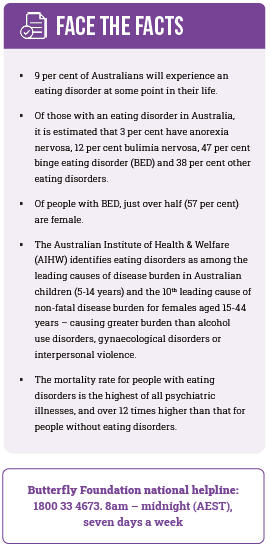

In late September the Federal Government launched a 10-year strategy that aims to prevent eating disorders in Australia and support those who experience them. The first ever national blueprint that addresses this complex mental illness couldn’t have come any sooner for the more than 1 million Australians – an estimated 4 per cent of the population – who live with an eating disorder in any given year.1

The Australian Eating Disorders Research and Translation Strategy 2021-2031 will help guide the development of a robust research ecosystem, which will in turn support a dynamic therapeutic space that can readily introduce new concepts to prevent illness, and better treat and support patients and their families.

Hopefully, it should also encourage and enable change at the state level.

For Western Australians suffering from eating disorders, timely access to services has been a long-standing issue.

Psychiatrists specialising in eating disorders have been advocating for greater investment for well over a decade, most recently calling for an investment of $25 million over four years to establish structured day programs for both youth and adults, as well as funded specialist inpatient beds within each area health service.2

The Centre for Clinical Intervention (CCI), WA’s only publicly available specialist clinical psychology service claims to have an average waitlist of 2-3 months, depending on care requirements. However, other reports say the waitlist could be as long as 8-9 months.

Across the continent, people with a lived experience of an eating disorder repeatedly report that access to care is patchy, inconsistently delivered, difficult to navigate, often not evidence-based and at its worst, they report it to be harmful. 1

The best available evidence suggests that most will not be identified when they present to the health system, 70 per cent of people with an eating disorder will not receive treatment and of those who do, only 20 per cent receive an evidence-based treatment. 1

Eating disorder charity, the Butterfly Foundation, maintains there are fewer than 40 public beds dedicated to eating disorders and about 120 private ones in all of Australia.

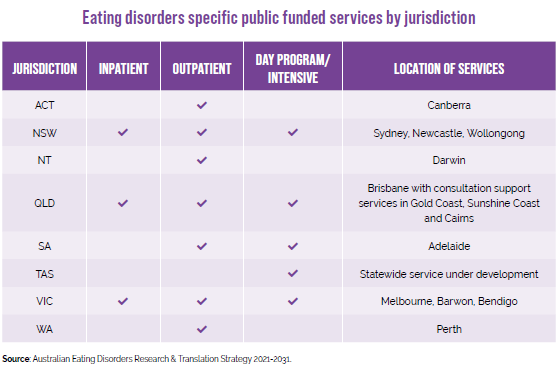

According to the national strategy, Western Australia shares the podium with the Northern Territory and the Australian Capital Territory for not providing publicly-funded specialist inpatient or day program services.1

(See table below.).

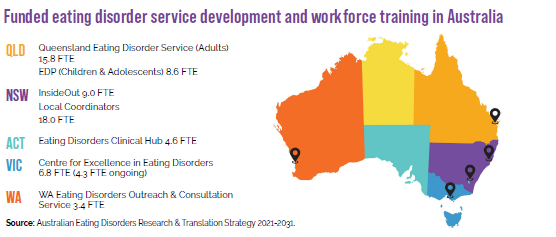

The national strategy document also refers to staffing levels (expressed as Full Time Equivalent FTE) of funded eating disorder service development and workforce training services, and organisations available in Australia. Once again, WA lags behind Victoria,

New South Wales, Queensland and the ACT. 1

The McGowan Government’s recent multi-million-dollar fillip to eating disorder services has, therefore, been welcomed across the sector.

Janet Fountaine, a nurse practitioner at WA Eating Disorders Outreach and Consultation Service (WAEDOCS), told Medicus the funding commitment was fantastic news for healthcare professionals and patients.

“We are very pleased that the Government has committed to allocating $31.6 million to expanding eating disorder services as part of the 2021-22 Budget,” Ms Fountaine said.

The WAEDOCS service, which runs out of NMHS, offers support to clinicians who see eating disorder patients as part of their everyday work. The service employs a nurse practitioner, clinical psychologist, psychiatrist, specialist physician, dietitian, clinical nurse specialist, and a peer support worker – all of whom reach out to public, private and community sectors to guide best practice.

Dr Lisa Miller, consultant liaison psychiatrist at WAEDOCS, also welcomed the State Government’s funding announcement.

“I look forward to the opportunity for Western Australians to be able to access an integrated continuum of care in seeking the best practice as outlined by the National Eating Disorder Collaboration (NEDC),” Dr Miller said.

The $31.6 million from the recent State Budget has been allocated to the Mental Health Commission (MHC) to expand the WA eating disorder specialist services, using a shared care approach that will bring together clinical and community services and help consumers to access and navigate the appropriate care throughout their recovery journeys.

Service design and delivery of the expanded services have been based on gaps in the system, identified as part of the Western Australian Mental Health, Alcohol and Other Drug Services Plan 2015-2025.

According to an MHC spokesperson, the process of designing the proposed services involved extensive consultation and engagement with consumers, carers, clinicians, community organisations and groups, and government agencies, as well as a review of evidence and research provided by the NEDC.

“Further to this, extensive research was carried out,

along with a current state assessment and a gap analysis including an inter-jurisdictional comparison of eating disorder services available across the country,” the spokesperson said.

Overall, it’s a positive outcome for the service, with the funding being used to expand WA’s eating disorder treatment services for people aged 16 and over, including pregnant women.

The expansion will include two dedicated multidisciplinary services, one each in the north and south metropolitan area, that will be accessible to people across WA.

Each will provide a triage service, intensive day programs, intensive clinical monitoring to provide support to people in the community, and specialist multidisciplinary outpatient clinics that include a step-down service for inpatients with eating disorders.

Those working in the eating disorders space have also acknowledged the difficulties experienced by patients transitioning from acute services in the public health system to sub-acute and community-based services.

The MHC hopes to address this particular challenge by employing patient transition coordinators, with a view to providing an integrated continuum of care according to the patient’s changing needs.

The need to have expertise across all stages of the disorder, not just for emergency situations in tertiary facilities has long been acknowledged.

An early start

Eating disorders do not discriminate and can affect anyone at any age. However, they commonly affect people at a critical developmental juncture during adolescence and young adulthood, between the ages of 12 and 25 years.

In WA, services for children and adolescents under the age of 16 are steered by Perth Children’s Hospital (PCH). The majority of inpatient admissions at PCH are admitted to Ward 4A via the emergency department. The average length of stay on Ward 4A for a young person with an eating disorder so far for 2021 is 20.97 days, up from 13.88 days in 2020.

However, Dr Aresh Anwar, Chief Executive of the Child and Adolescent Health Service (CAHS) said that this does not necessarily reflect an increase in the severity or complexity of the illness, but rather an active change in treatment pathways that provide more therapeutic input for the young person and their family.

“CAHS is actively looking at options to respond to this very serious health issue. The introduction of a dedicated inpatient eating disorder unit in 2022 is one of the options currently being explored,” Dr Anwar said.

“CAHS is actively looking at options to respond to this very serious health issue. The introduction of a dedicated inpatient eating disorder unit in 2022 is one of the options currently being explored,” Dr Anwar said.

“In 2022, the eating disorder service plans to re-introduce a day program, and explore ways to develop consultation and liaison pathways to ensure other service providers are skilled and equipped to respond to an eating disorder in the early phases before admission is required.”

The transition from child and adolescent to adult services can also be a difficult process.

After a young person turns 16, they can be left with nowhere to go. The MHC’s planned patient transition coordinators should help to address the challenges that arise during this crucial phase. But with expanded MHC services expected to commence only from July 2022, existing patients may find themselves in a bind.

Mia,* a young woman with lived experience of an eating disorder, told Medicus that despite being a patient under the Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service (CAMHS), she was considered too old for Princess Margaret Hospital (PMH) at the time.

“My CAMHS psychiatrist fought very hard to have PMH’s outpatient service take me on, but I was considered too old for treatment. I was 16,” Mia recalled.

“Luckily I was allowed limited access to services when they realised I was diagnosed at PMH at the age of 15. I was allowed to see a doctor weekly who would monitor me physically.”

Mia said finding an effective treatment pathway in the public system was difficult, and she attended a range of services including PMH, CCI, Fremantle Hospital and the Bentley Adolescent Unit.

“I still think there’s a long way to go in improving ease of access to equal care in the public system.

“My treatment has been managed extremely well in the private system. My treating team are all specialists in the area and have been incredibly dedicated to providing me with the best treatment, while also managing my co-morbid mental health diagnoses,” Mia said.

The only private provider of inpatient eating disorder services in WA is Hollywood Private Hospital, which also offers an outpatient program focused on recovery and helps participants develop the knowledge and skills to overcome unhelpful eating behaviours and mindsets.

It is suitable for patients 16 years of age and older with less severe eating disorders, or for patients wanting to build on gains made in a recent inpatient stay for an eating disorder.

*Name changed upon request

Hope ahead?

The public health system may be weighed down by the rising demand for access to services, yet green shoots are appearing in the system.

The South Metropolitan Health Service (SMHS) is establishing an Eating Disorder Intensive Outpatient Program (EDIOP) designed to provide a multidisciplinary approach to the treatment of young people with a diagnosed eating disorder, residing in the SMHS catchment.

According to an SMHS spokesperson, the program, which will be fully operational in early 2022, will deliver both individual and group care that focuses on education, support, self-compassion and emotional processing.

In addition, State and Federal governments are at the final stages of discussion for the residential eating disorders centre project planned for the Peel Health Campus. This is part of the $4 million investment from the Federal Government announced in February 2019.

An early identification service is also in the works, with the MHC confirming details were still being developed.

Ms Fountaine said GPs and other health practitioners will continue to have access to education and training on early identification and prevention via WA Eating Disorder Outreach Clinic (as they do now).

“We respond to a significant number of calls per week from clinicians across the State seeking support for their eating disorder patients,” she said.

“It’s common for GPs to call us asking about unusual food-related behaviours and the best way to sensitively intervene and navigate to appropriate services.

“Early identification and treatment are key to recovery for eating disorders. GPs are ideally placed to effect this and at WAEDOCS, we support, educate and empower GPs daily to feel confident in managing the complexity of caring for people with eating disorders.”

Dr Susie Cann, a GP who specialises in eating disorders said that although it can be tempting to provide funds to tertiary services where significantly unwell patients end up, the reality is that early intervention provides the best spend of dollars in terms of limiting significant disruption to individuals, families and communities.

“Every patient saved from a hospital admission via early management represents significant savings to the health system,” Dr Cann said. (You can read more about Dr Cann’s experience and advice for GPs on p24).

There’s still a long way to go though, as GPs like Dr Cann and their patients regularly encounter gaps in the system. But with the national strategy shining the spotlight on the issue and the State Government placing much-needed funding on the table, eating disorders are finally getting the recognition they deserve. The appetite for real, tangible change on the ground is growing.

References available upon request.