Blog

Ambulance ramping at record high

Monday December 21, 2020

Inaction by the McGowan Government is causing complete chaos for patients in WA’s emergency departments.

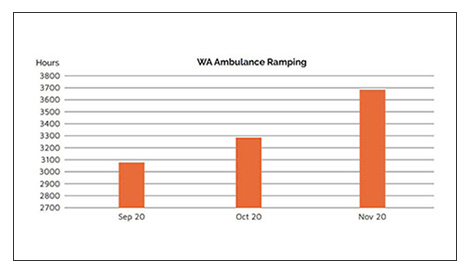

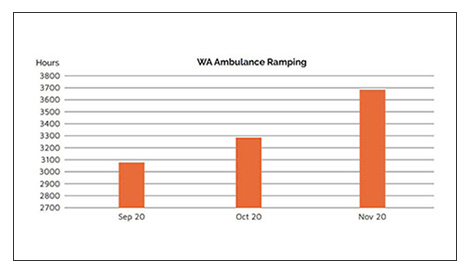

September 2020 marked a dark month in Western Australia’s history – for the first time ever, ambulance ramping exceeded 3,000 hours in a calendar month. “Catastrophic” and “terrible” is how the AMA (WA) characterised 3,000 hours of ambulance ramping, particularly for the elderly, who are the most likely people to be stuck on an ambulance trolley out the front of our emergency departments.

“Non-existent” and “indifferent” is how the AMA (WA) characterises the McGowan Government’s political response to this health crisis. The Premier and Health Minister Roger Cook have gone AWOL. COVID-19 is not the problem. Influenza is not the problem. Patients seeking urgent medical care are not the problem. Cleaning and servicing of ambulances is not the problem.

Political inaction is the problem.

An absence of political understanding or will to address systemic health system issues such as hospital capacity, has led to WA’s EDs being overrun.

October 2020 levels exceeded September 2020 levels by 7 per cent.

November 2020 levels exceeded October 2020 levels by 12 per cent.

ED Physicians on WA’s Ambulance ramping crisis

The AMA (WA) approached emergency department doctors at Fiona Stanley Hospital, Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital and Royal Perth Hospital to share on-the-ground views of the everyday battles they face and the actions they are taking to manage record-breaking ambulance ramping over the past few months. We chose to protect the identities of these doctors so they could share their opinions frankly and without fear of reprisal. The AMA (WA) thanks these clinicians for their insights and their service.

“The inn is full”

ED Physician Royal Perth Hospital

Overcrowding at Royal Perth has been a serious risk for several years, but the past few months have been exceptionally bad. We have ‘achieved’ four of the five worst months of ambulance ramping ever. Patients can’t get into our ED because patients can’t get out – the inn is full.

The wait for inpatients beds has been extraordinary, daily waits often totalling hundreds of hours a day, with the ‘average’ time to get a bed on an RPH ward after referral being 2.5 hours. Beds cannot be opened, as wards deal with budget constraints and staff shortages.

Overcrowding has contributed to the stress of a busy year. We care deeply for our patients, and our nursing and medical colleagues are amazing. However, the escalating sense of exhaustion and the constant sense of ‘crisis’ is wearing us down.

WEAT seems irrelevant in this current environment, and simply a tool used to indicate that ‘ED’ is where the ‘problem’ must be, but that is not the case.

Overcrowding, and the resultant ramping, must have whole-of system solutions. More beds to allow patients out the back end, and more staff to allow more processing power, but how do we convince administrators when the purse is empty?

“My opening gambit when I see a patient is to apologise for us failing to meet their needs.”

ED Physician Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital

Ramping is the final domino of a healthcare system failing to meet its emergency access targets. Ramping has negative impacts on both ambulance and waiting room patients, as both cohorts are competing for the same emergency bed. They both suffer the same consequences for not having access to that bed.

Ramping leads to increased DNW (“did not wait” patients), and delays in diagnosis and time-critical management. The emergency department is put under pressure to discharge patients early, or to look after them as inpatients long after the decision to admit has been made.

When patients cannot be assessed, other inefficiencies are introduced in an attempt to mitigate risk. This results in more tests being ordered, further overburdening our imaging services and paradoxically lowers our admission threshold.

My opening gambit when I see a patient is to apologise for us failing to meet their needs. Patients are left unhappy and dissatisfied with their service, as clinicians and nurses are left with a sense of futility and exhaustion.

Short-term and quick-fix solutions to decrease endemic ramping have failed. Short-term solutions at the ED level have involved ringfencing capacity for access block independent flow (fast track, ED discharges and observation ward admissions), and by increasing virtual capacity through hot swapping beds (PIT stop), seeing patients in non-gazetted areas (triage, waiting room) and admitting directly from the waiting room.

Longer-term solutions should look at not only the number of inpatient beds required, but how effectively those inpatient tertiary beds are used. This may include how beds are managed over weekends and out of hours. Tertiary beds can be used more effectively by improving access to imaging and diagnostic services as well as early consultant-led inpatient decision-making and disposition planning. Expedited discharges will require increased access to home support services, specialty clinics and an increased capacity in transitional care as well as inpatient mental health beds and community clinics.

Sir Charles Gairdner Hospital’s ED capacity is monitored using a traffic light system. When that capacity is exceeded, a disaster is called. With increased ramping, we are seeing a hospital whose status is rarely green and where every week, there is a disaster.

SCGH has welcomed the commencement of a Capacity Command Centre, which was inaugurated earlier this month. Whilst implemented on a temporary basis, it is the first step in recognising that long-term solutions to endemic ramping can only be met by a system-wide coordinated response, delivered across multiple facilities and services.

ED docs look to new models of care during current ramping crisis

ED Physician Fiona Stanley Hospital

The past year has been dominated by COVID-19, which is perhaps why ambulance ramping has flown under the radar. Ramping results in sub-optimal patient experiences and clinical outcomes, makes emergency departments less safe, and limits the ambulance service’s capacity to respond to the community.

There are particular sub-groups of patients over-represented in our EDs such as mental health patients, the frail aged, and those with violent and disturbed behaviour conveyed to ED by WA Police. The ambulance ramp and ED is frequently an inappropriate environment for these patients, who would be far better served by alternative models of care that lie outside ED.

The ED at Fiona Stanley Hospital, with the support of hospital executive, and in partnership with St John Ambulance, has commenced working on an Ambulance Tele-Triage and Assessment model. That will allow decision-making outreach to diversify arrival options other than the ramp queue, and support ongoing growth of community-based models of care.

Whilst we do not believe the current crisis will be easily solved, we do believe innovation in models of care is the only way forward and the skills and adaptability of emergency physicians will play a pivotal role in achieving these system innovations.